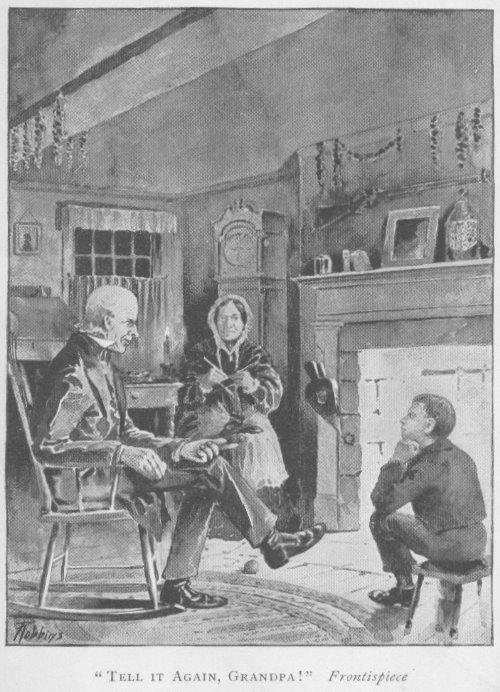

Figure

1: Tell It Again Grandpa!

BENEATH OLD ROOF TREES

BY

ABRAM ENGLISH BROWN

AUTHOR OF "HISTORY OF BEDFORD" "BEDFORD OLD FAMILIES"

"GLIMPSES OF OLD NEW ENGLAND LIFE"

AND "FLAG OF THE MINUTE-MEN"

BOSTON

LEE AND SHEPARD PUBLISHERS

10 MILK STREET

1896

TO

THE SOCIETIES ORGANIZED TO PERPETUATE THE

HONOR OF THE BRAVE MEN AND WOMEN,

THROUGH WHOSE SACRIFICES

THE AMERICAN COLONIES OBTAINED THEIR FREEDOM,

This Volume

IS GRATEFULLY INSCRIBED

Figure

1: Tell It Again Grandpa!

WHILE speaking on the battlefield at Lexington with tourists from the city of Philadelphia, allusion was incidentally made to other towns than those usually mentioned in this connection; whereupon I was at once politely met with the honest inquiry, "What did they have to do with it?"

My object in this volume is to answer that question, showing in a story-like manner the part taken by many towns in the opening events of the Revolution.

In offering this work to the public, I desire to acknowledge gratefully the sources from which aid has been obtained ; but they have been so numerous that I refrain from mentioning any published works, lest I may inadvertently omit some.

Manuscript records of towns and churches have been freely consulted through the courtesy of their custodians to whom I am indebted. The many interviews with venerable men and women herein recorded have been to me occasions of great pleasure, and I trust will result in lasting benefit to all who peruse these pages.

This volume being one of a prospective series, "Footprints of the Patriots," treats of only a small portion of the towns identified with the opening Revolution.

It is my purpose to consider the other towns as they appear in the widening circle from which came the ready response to the memorable alarm.

If the reader shall be aroused to a keener appreciation of the cost of our national heritage, and to a higher standard of citizenship beneath its star-spangled emblem, the work will not have been in vain.

With that hope for an impelling motive in the future as it has been in the past, I remain the friend of the reader.

"'Tis like a dream when one awakes,

This vision of the scenes of old;

'Tis like the moon when morning breaks;

'Tis like a tale round watchfires told."

"Surely that people is happy to whom the noblest story in history has come down through father and mother, and by the unbroken traditions of their own firesides." --SENATOR GEORGE F. HOAR, Oration at Plymouth, December, 1895

Table of Contents

"WHAT DID THEY HAVE TO DO WITH IT?" 3

INTRODUCTORY.- SOME OF THE GENERAL FACTS OF THE OPENING REVOLUTION 6

CHAPTER III 15

IMPORTANT MESSAGES. -- PARSONAGE GUESTS. -- MIDNIGHT MESSENGERS. -- ECHOES OF THE LEXINGTON BELFRY 15

CHAPTER IV 20

BELFRY ECHOES CONTINUED. -- JOHN PARKER'S STORY, JOSHUA SIMONDS'S STORY 20

CHAPTER V 27

MORE BELFRY ECHOES.- BOSTON POOR 27

CHAPTER VI 31

THEODORE PARKER. -- A BELFRY LISTENER 31

CHAPTER VII 35

CHAPTER VIII 42

CHAPTER IX 55

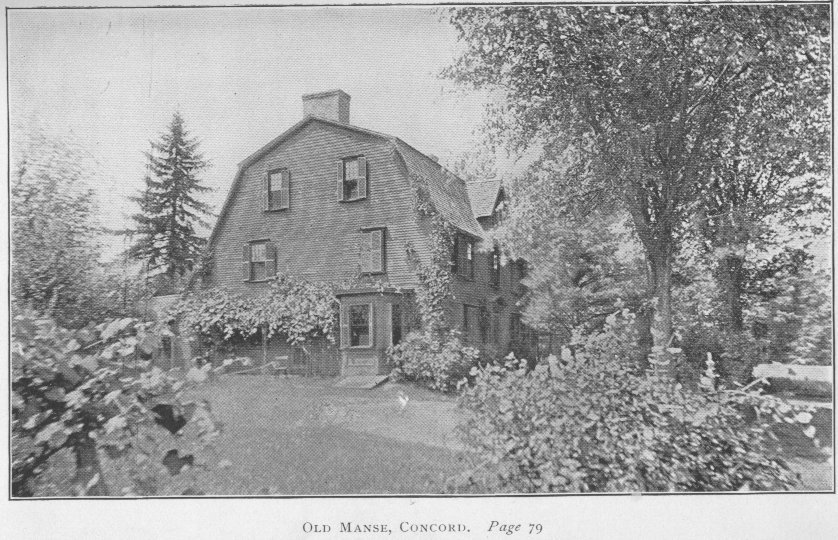

OLD MANSE OF CONCORD AND ITS MINISTERIAL OCCUPANTS. -- CUPID IN THE REVOLUTION 55

OLD MANSE. 55

CHAPTER X 67

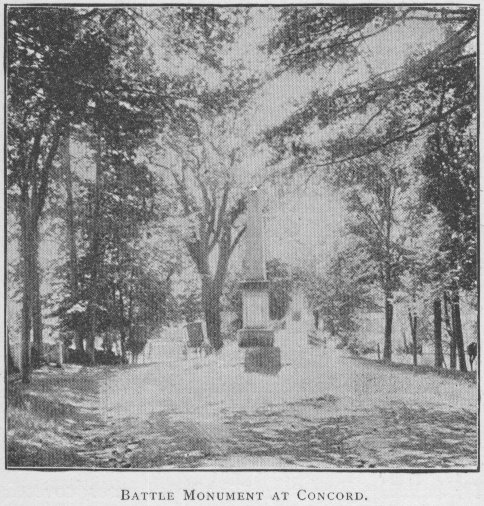

TOLD AND RETOLD. -- INCIDENTS OF CONCORD FIGHT 67

CHAPTER XI 74

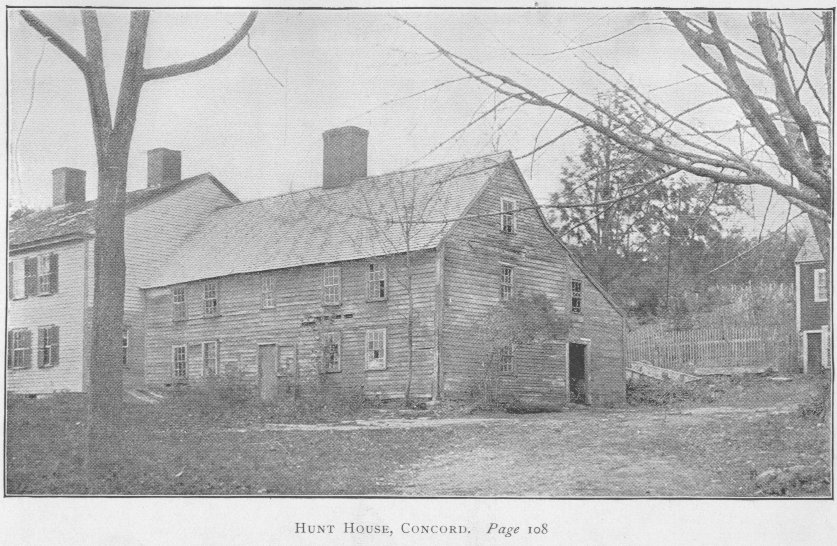

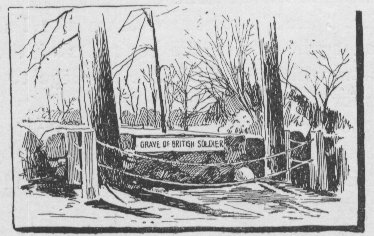

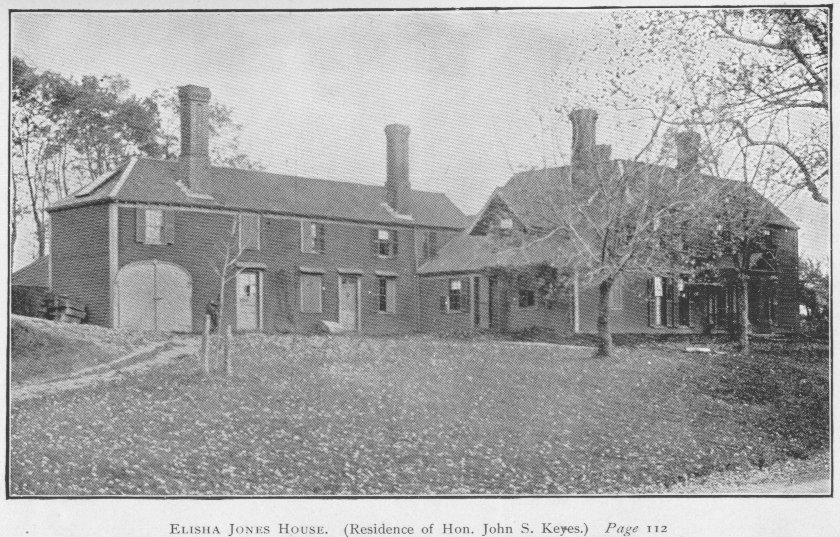

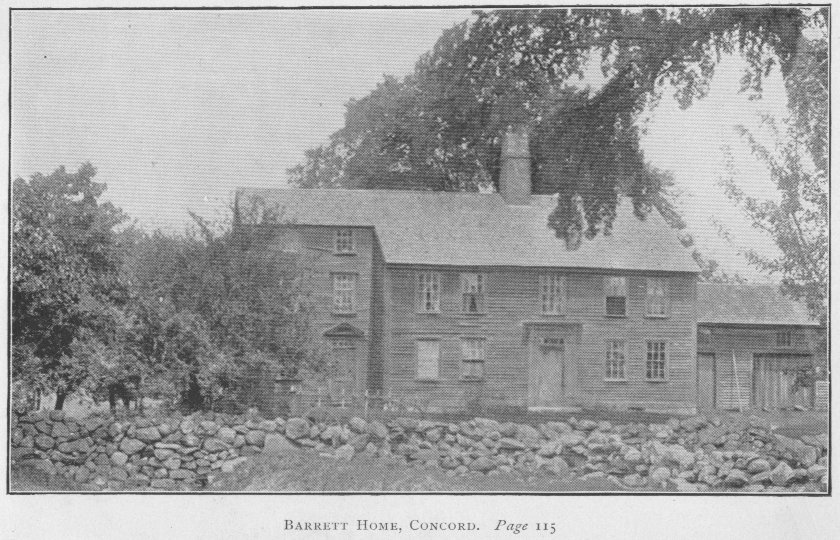

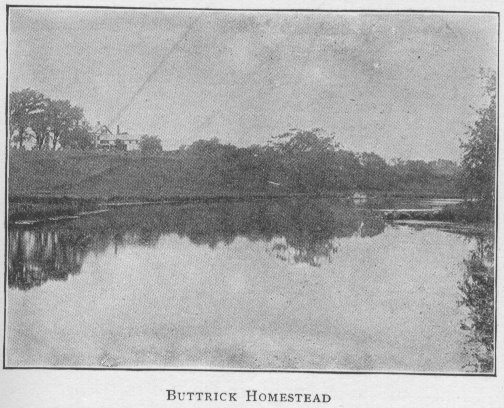

CONCORD HOMES OF HISTORY IN 1775 74

CHAPTER XII 79

CHAPTER XIII 89

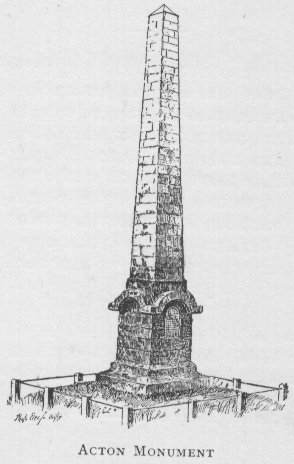

FOOTPRINTS OF ACTON PATRIOTS 89

CHAPTER XIV 95

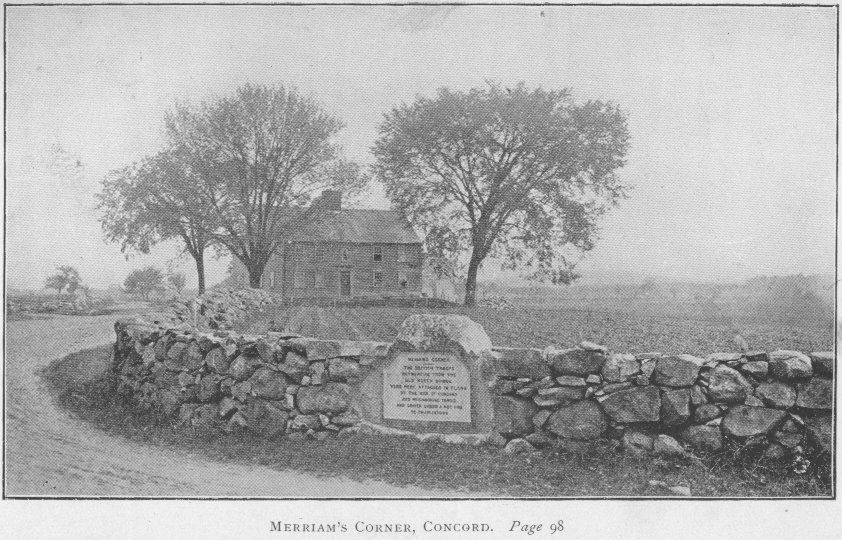

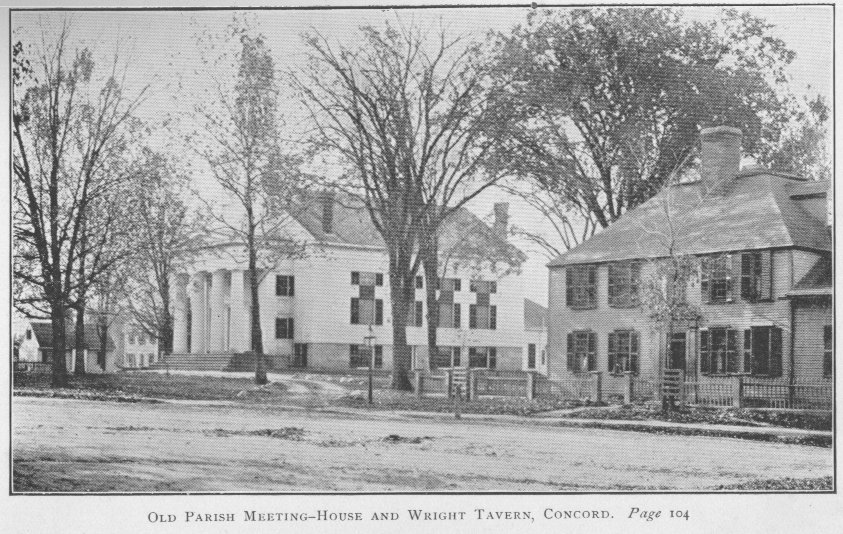

SPEECH OF REV. JAMES T. WOODBURY. -- EAGLE IN CONCORD FIGHT REV. JAMES T. WOODBURY'S SPEECH 95

CHAPTER XV 106

FOOTPRINTS OF THE PATRIOTS AT BEDFORD. THROUGH THE OLD BURIAL-GROUND AT BEDFORD WITH A NONAGENARIAN 106

CHAPTER XVI 117

THE OLD COLONIAL BANNER AND FLAG OF THE MINUTE-MEN OF BEDFORD 117

CHAPTER XVII 123

CUPID'S HEIRLOOM 123

CHAPTER XVIII 127

CHAPTER XIX 135

BILLERICA PATRIOTS. -- HILL HOMESTEAD. -- PROVISION FOR THE ARMY. -- MRS. ABBOTT'S STORY 135

CHAPTER XX 140

THE STORY OF MENOTOMY. -- THE RUSSELL FAMILY STORE. -- STORY OF WHITTEMORE FAMILY. -- CAMBRIDGE. 140

CHAPTER XXI 153

GENERAL ARTEMAS WARD. -- THE OLD HOMESTEAD SHREWSBURY 153

CHAPTER XXII 161

CHAPTER XXIII 170

THE revival of interest in Napoleon Bonaparte inclines many to long to visit the scene of his fatal conflict. But Waterloo, described and painted by pen and pencil over and over again, when viewed in connection with its results to the, world, is not comparable to the battlefield of Middlesex.

Good citizenship is patriotism in action. It is not necessary that one should face the bullets of he enemy on the field of battle in order to evince true patriotism. He who loves his home, his native town, and his country, and is ready to make sacrifice for their honor and welfare, is the good citizen. In him the germ of patriotism is well developed.

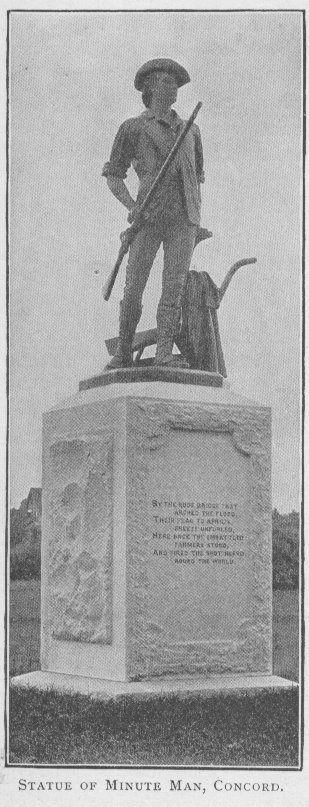

This is seen in the great company of intelligent people who make pilgrimages every year to Lexington, Concord, Bunker Hill, and other places of historic interest. Each recurring anniversary emphasizes the fact. No true citizen can cross the green sward of Lexington Common, gaze upon the bronze "Minute-man" at Concord, or press the turf of Bunker's height, without feeling the blood course more rapidly in his veins as he makes new resolutions of better citizenship.

We find nothing of a sanguinary character of the scenes that were enacted on the memorable 19th of April, 1775; for the war-drums throb no longer, and the battle-flags are furled. The bayonets of the red-coated soldiers glisten no more ominously in the gray dawn of the breaking day, and the musket of the yeoman hangs useless among the reminders of the past. But within easy access of New England's metropolis are many existing reminders of that most significant uprising, and the person for whom a recital of the "oft-told tale" of the battlefield would prove tedious will find enough of interest in the story of things and places that existed when the wild crash of musketry broke the stillness of that April dawn.

While the scene of carnage was at Lexington and Concord, and on the entire line of retreat, it was from all Middlesex that the yeoman soldiery came; and the entire Province was in arms before nightfall, and all New England was astir before another sunset. I would not abate one "jot or tittle" from the accumulated honor justly due Lexington or Concord, but I would remind all young people that the only limit to the response was the primitive means of spreading the alarm. A preconcerted signal was so general that it required but "a hurry of hoofs in a village street," or the crack of a musket from a chamber-loft, to carry on the alarm from town to town. When the immortal scroll of that day was made up, there appeared upon it forty-nine names. These were from seventeen different towns, ten of which were in Middlesex, four in Essex, and three in Norfolk Counties. But more than twice this number of towns responded to the alarm before the enemy were back within protection of their ships of war.

It is natural that the tourist should find his interest centre at Lexington and Concord; but if he would trace the footprints of the patriots, he must follow them in the dew of that early morning from their remote homes to the scene of conflict, and in the evening by the blood of the martyrs, who, early slain, were borne lifeless to their homes.

The general uprising of the colonies on the 19th of April, 1775, was the natural outcome of the treatment to which they had been subjected. They had always claimed the liberties of Englishmen, acting upon the principle that the people are the fountain of political power, an that there can be no just taxation without representation. Every act of the British ministry tending to undermine these principles served but to whet the blade of righteous indignation. The acts of Parliament "for the better regulating the government of the Province of Massachusetts Bay," and "for the more impartial administration of justice," were regarded as blows aimed at the liberties of the people, and, when undertaken to be carried into effect by the local authorities at Boston, created a commotion throughout the colonies. The positive dealing with the small tax on tea was but the outcome of a failure to maintain their rights by strong reasoning, firm resolves, and eloquent appeal for a series of years. It was the boldest stroke of the people up to that time, and, although struck in Boston, received a hearty approval from the remotest hamlet, through the ringing of bells and other signs of joy. The punishment intended for Boston by the Port Bill, which took effect June 1, 1774, was a blow felt and resented at the remotest border. Its execution devolving upon Thomas Gage brought general contempt upon one who had so recently been proclaimed the governor with great applause, and Fanueil Hall had been the scene of animating festivity in his honor. From 1767, when the first addition was made to the troops which commonly formed the garrison of Castle William, there had been a growing unrest among the Provincials, strengthened by each new arrival quartered within the town, and becoming unbearable at the massacre in King Street, on March 5, 1770. Each anniversary of this event served as another occasion for declaring the charter rights of the Province, and, although calling forth the expression of different sentiments, was continued until the Declaration of Independence cleared the way for a new anniversary, and the 4th of July, instead of the 5th of March, became the day of America's patriotic expression.

One needs but refer to the manuscript records of the small towns of the colonies to be duly impressed with the approval of each act of the leaders in Boston. The record of sympathy expressed for Boston and Charlestown when the Port Bill went into effect, the memoranda of provisions forwarded for the relief of the distressed, together with the solemn league and covenant against the use of British goods into which they entered and boldly spread upon their records, attest the intensity of feeling which cemented the people more closely together as the months of trial succeeded one another, all of which found civil expression in the acts of the Committee of Correspondence, and also in the convention of Aug. 30, 1774, at Concord, when one hundred and fifty delegates from the towns of Middlesex County placed upon record, "No danger shall affright, no difficulty shall intimidate us; and if, in support of our rights, we are called to encounter even death, we are yet undaunted, sensible that he can never die too soon who lays down his life in support of the laws and liberties of his country."

Following close upon the memorable convention of Middlesex came the Provincial Congress, which assembled in the meeting-house of Concord, the hostile preparations, the clash of arms, and the general uprising of the people.

One hundred and twenty years have passed since the embattled farmers struck the first blow for liberty, but many reminders of that day are yet to be seen. Hills over which Revere galloped on his midnight ride have been carried into the valleys through which he made rapid pace; but many a hearthstone that glowed with the embers of patriotism is still the pride of a thrifty owner, who rejoices that the same roof which protects him sheltered his grandfather, who at the same door gave a parting blessing to wife and children as he hastened to the scene of conflict. Such homes, possessed and cared for by those who have there received the story of personal experience from honored sires, are monuments to which all would gladly revert. These, and the many other reminders of the footprints of the patriots, have their lessons of good citizenship for all.

I have spent much time, during a score of years devoted to historical writing, in visiting such homes throughout New England, and in conversation with the widows of those who had personal experience in the army, also with the children who have had the story of sacrifice from fathers who suffered in the field, camp, or hospital, and from mothers whose sufferings were beneath their own roofs. The widows and children of soldiers of the Revolution had become very scarce when I began my research; but grandchildren have been often met who received indelible impressions of the struggle of the colonists, while fondled in the arms of those who were actors in the Revolution.

The result of my research has from time to time been given to the public in story through the daily press. Realizing that such a medium, in the main, is as fleeting as the day, I have been prompted to gather my stories into a more enduring form for the benefit of the many whom I now ask to visit the scenes. Familiarity entitles me to invite the company of all who have entered into the labors of the patriots of '75.

BOSTON is our starting-point. We make but a short journey into Middlesex County, having the restless army of Gage in view as they start on their "holiday excursion," before we are in the midst of the scenes that witnessed the flight of the redcoats, and their steady pursuit by the rough-clad yeomen. The very ground has tongues to tell the story of that heroic clay. The memorials that patriotic hands have set to mark the deeds that were done recount anew the romantic valor, the courage that could not tire, and the resolution that knew no compromise.

As we go over that ground we will listen again to the words of the great patriot Samuel Adams, spoken as the sun was rising over the hills of Lexington: "What a glorious morning for America is this!" It matters not whether this morning's exclamation was the evidence of prophetic wisdom; certain is it that Samuel Adams1was the great seer of his time, and, having the sight, he spared nothing to hasten the dawn of a better era for America. Tardy, indeed, is the gratitude of a great nation shown by the failure to appropriately mark his resting-place in Granary Burial Ground in Boston, where in like obscurity rests his honored associate, John Hancock2. In passing we will not fail to commend the people of Lexington, who have provided the horizontal slab, in the form of a shield, which tells us where Hancock and Adams were when the attack was made upon the Lexington company. Every child is familiar with the story of Lexington and Concord. He knows --

"How the British regulars fired and fled;

How the farmers gave them ball for ball

From behind each fence and farmyard wall,

Chasing the redcoats down the lane,

Then crossing the fields to emerge again

Under the trees at the turn of the road,

And only pausing to fire and load."

It is not my purpose to recount the events of the opening Revolution familiar to the most careless student of history; but I deem it advisable to give a brief outline of facts, in order to show their bearing upon the acts of other towns than those commonly mentioned.

The uprising, so general throughout the Province of Massachusetts Bay and in the adjoining country, was the result of months of agitation. During this time the best preparations possible were made, although a hostile army was in possession of the leading seaport, and Tories on either hand were using every possible means to inform the king's agent of the movements of his "rebellious subjects." Their own domestic cares were greatly increased by the support of the poor of Boston, who were forced to leave their homes, and flee to the country. Meetings for consultation were frequently held, although forbidden by the waning power of the governor. They withdrew their stock of powder, etc., from the Quarry Hill Magazine at Charlestown; put in trim their old muskets with which they served the king before Louisburg; whetted the bayonets that had pierced the hearts of French and Indians; moulded their tableware into bullets; and listened at their rude altars for the God-given message delivered to them by patriotic pastors.

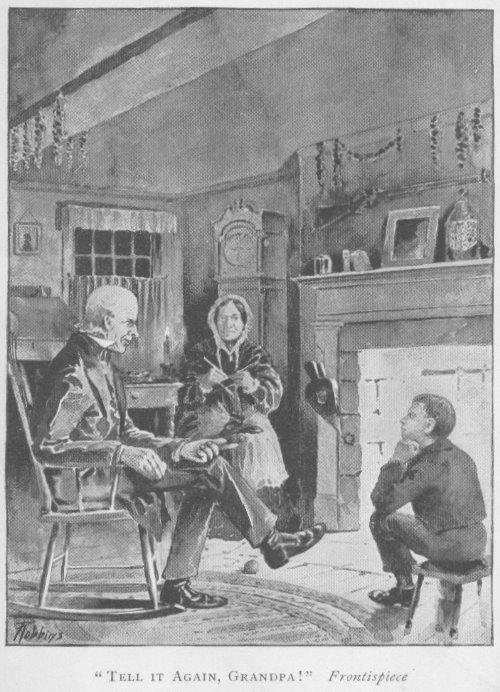

Each and all of these movements were quickly communicated to General Gage by their enemies at their own doors. The general stock of powder for the use of the Province was left in the powder-house; and this was removed by order of. General Gage, at the instigation of William Brattle of Cambridge, and lodged at Castle William.

Figure

2: Old Powder House, Somerville

Believing that the guns which they had manned for the king were liable to be turned on them, they did not hesitate to appropriate them to their protection. The old battery at Charlestown, where the Navy Yard now is, was dismantled in sight of the ships of war which lay opposite; and the guns were removed by the patriots, and carried into the country, despite the vigilance of the British officers. But the object of the patriots was not to overturn, but to preserve. They claimed their ancient rights and liberties, regarding ease, luxury, and competency as nothing, so long as the rights enjoyed by their ancestors were denied to them.

Each town had its militia, an organization of long standing, and its minute-men, organized by order of the Provincial Congress on Oct. 26, 1774, which was an outcome of the General Court ordered to convene at Salem by Governor Gage. They cheerfully paid their taxes over to one of their own number, who had been made Province treasurer, -- Henry Gardner of Stow. Each town voted money freely to arm, equip, and discipline "Alarm Lists Companies." The leading citizens were made the officers of the companies; and military drill on the towns' common or training-field as frequently supplemented by adjournment to the meeting-house, where religious services were held. They were exhorted by their ministers to prepare to fight bravely for God and their country.

The patriots were aware of the injury to their cause by the Loyalists, but they saw them make no successful attempt at organization until General Timothy Ruggles of Marshfield headed one. He was a great leader of the Loyalists, or Tories as they were derisively called. Their requirements were that all who joined it should at the risk of their lives oppose all acts of constitutional assemblies, such as committees and congresses. This Marshfield association had the protection of the king's troops under Captain Balfour.

An exultant Tory letter of the time says of them: "The king's troops are very comfortably accommodated, and preserve the most exact discipline; and now every faithful subject to his king dares freely utter his thoughts, drink his tea, and kill his sheep as profusely as he pleases."

It was during these midwinter days of anxiety and expectancy throughout the towns that Salem just escaped the beginning of hostilities, and the honor of being the Lexington of the Revolution. Some brass cannon and gun-carriages were deposited there, and Colonel Leslie made a Sabbathday excursion to seize them. Knowing the habits of the New England people for church attendance, he landed at Marblehead, and in the afternoon of Feb. 26, while the people were at meeting, started for Salem. His object was suspected, and a messenger despatched to the neighboring town. The desired materials were on the north side of Old North Bridge. This was built with a draw for the passing of vessels; and before Colonel Leslie reached there, the people had it raised. His order to lower it was refused, and their action sustained by the statement, "It is a private way, and you have no authority to demand a passage this way." The officer then made preparations to cross the river in two large gondolas that lay near. But their owners made good their objections by scuttling them. A few of the soldiers tried to prevent this; and in the scuffle which attended it bayonets were used, and it is recorded that blood was spilt. At this juncture a clergyman of Salem, Rev. Mr. Barnard, interfered; and a compromise was effected, whereby the troops retired without having accomplished their purpose. In fact, they had injured their general cause; for the movement had aroused the people to the point of action not before reached. The alarm got to Danvers in time for the minute-men of that town to rally and march to Salem, arriving just as the British were leaving town.

The rhymester of the day noticed this expedition. After the description of the arrival at Marblehead is the following: --

"Through Salem straight, without delay,

The bold battalion took its way;

Marched o'er a bridge, in open sight

Of several Yankees armed for fight;

Then, without loss of time or men,

Veered round for Boston back again,

And found so well their projects thrive,

That every soul got home alive."

The people of the country were in sympathy with those in the larger towns. Boston was their guide. They watched the movements of the patriots there with great interest. The sentiments of the Massacre anniversary orators were freely indorsed in all the towns where patriotism prevailed. When one of their own number suffered violence they were ready to demand redress.

Early in March of 1774, Thomas Ditson, Jr., a citizen of Billerica, of thirty-four years of age, being in Boston, was seized by the British troops on the pretence that he was urging a soldier to desert; without any examination kept a prisoner until the following day, when he was stripped, tarred and feathered, and dragged through the principal streets on a truck, attended by soldiers of the Forty-seventh Regiment, under command of Colonel Nesbit, to the music of "Yankee Doodle," the original words of which, it is said, were then first used. This outrage produced great indignation; and the selectmen of Boston communicated by letter the case to the selectmen of Billerica, who presented a remonstrance to General Gage, and submitted the case to a town meeting. The town thanked the Boston authorities "for the wise and prudent measures" they had taken, expressed its dissatisfaction with the reply of General Gage, and instructed them to carry the case to the Provincial Congress. The man lived, and by his presence in Billerica and neighboring towns did more to the injury of the cause of the king than he could have done by inducing a whole company to desert. The indignation of the voters of Billerica is doubtless implied in an order "to look up the old Bayonets," which was passed at a town meeting held soon after Mr. Ditson's abuse.

To prevent the troops in Boston from being supplied with materials for hostile operations, the town also voted not to permit any team "to Load in, or after loaded, to pass through, the Town, with Timber, Boards, Spars, Pickets, Tent-poles, Canvas, Brick, Iron, Waggons, Carts, Carriages, Intrenching Tools, Oats," etc., without satisfactory certificate from the Committee of Correspondence.

General Gage knew that despite all his vigilance the patriots were gathering military stores, and their repositories were the objects of his jealous eye. A rumor was abroad that he had determined to destroy them; this led the Committee of Safety to establish a guard, and to arrange for teams to remove the stores to places of greater safety, in case of alarm. To make the arrangements more perfect and effective, couriers were engaged in Charlestown, Cambridge, and Roxbury to alarm the people. What better plans could have been made for each town to have some part in the decisive action, let it come in the full light of day, or under cover of the darkest shadow of night?

Officers of the king's army were sent out to Concord and elsewhere to spy out the situation, make plans of the roads, etc. They were well disguised, but detected and watched, and the people made doubly vigilant3. On the 30th of March, eleven hundred men were sent out through Jamaica Plain with an eye to intimidate the citizens; but they saw an uprising people well armed, and returned without important incident, only such acts of damage as any company long pent up in a town would naturally commit when passing through an enemy's territory.

The month of April opened with intelligence that re-enforcements for the king's army were on the way to Boston. Together with this news came that of the declaration of Parliament to the king, that the opposition to legislative authority in Massachusetts constituted rebellion, and also the answer of his Majesty to Parliament, that "the most speedy and effective means" should be taken to put the rebellion down.

Not only did the king's messenger require haste, but that of the Provincial Congress as well.

On the 5th the Congress adopted rules and regulations for the establishment of an army; on the 7th it sent a circular to the Committee of Correspondence, "most earnestly recommending" to see to it that "the militia and minute-men" be found in the best condition for defence whenever any exigency might require their aid, but, at whatever expense of patience and forbearance, to act only on the defensive; on the 8th it took effectual measures to raise an army, and to send delegates to Rhode Island, New Hampshire, and Connecticut to request their co-operation; on the 13th it voted to raise six companies of artillery, pay them, and keep them constantly in exercise; on the 14th it advised the removal of the citizens of Boston into the country; on the 15th it appointed a day of fasting and prayer. Having done all in their power, they seemed anxious to again commit their cause to the Almighty.

The days which intervened between the adjournment of Congress and the beginning of hostilities were spent in busy preparations for the inevitable. The Committees of Safety and Supplies usually met together, and were in session at Concord on the 17th, when they adjourned to meet at Menotomy.

While the Provincials were thus active, General Gage was making exertion to secure supplies for camp service; but the patriots made every possible exertion to prevent it, both in Massachusetts and New York.

Worried by the importunities of the Tories, and distressed by the energetic measures of the Whigs, who "unknown to the Constitution were wresting from him the public monies, and collecting war-like stores," it is not strange that he decided upon the action of the night of April 18.

Figure

3: A painting

A MOVEMENT of Gage's on the 15th looked suspicious to Dr. Warren, who sent out a messenger to Hancock and Adams, then at Lexington. It was this intelligence that prompted the Committee of Safety, of which John Hancock was chairman, to take additional measures for the security of the stores at Concord, and to order, on the 17th, cannon to be secreted, and a part of the stores to be removed to Sudbury and Groton. On the 18th (Tuesday) Gage's officers were stationed on the roads leading out of Boston, to prevent intelligence of his intended expedition that night. These officers dined at Cambridge. The patriot committees also met that day in Menotomy--West Cambridge (Arlington). Some of the Committee remained to pass the night at Wetherby's Tavern. Devens and Weston started in a chaise towards Charlestown, but soon meeting a number of British officers on horseback, returned to warn their friends at the tavern.

They waited there till the officers passed, and then rode to Charlestown4.

Figure

4: Lexington Parsonage

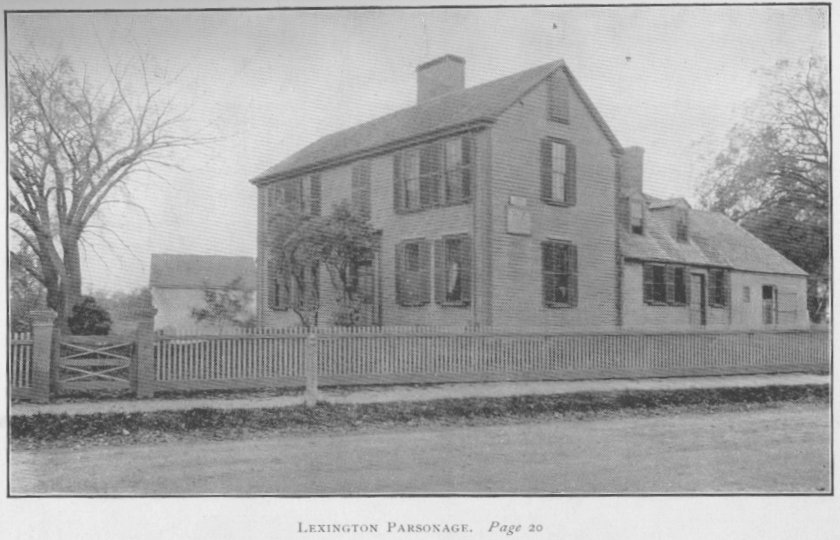

Mr. Gerry's letter was delivered by a messenger who took a by-path to the Lexington parsonage. The reply is worthy of notice.

"LEXINGTON, April 18, 1775.

DEAR SIR, --I am obliged for your notice. It is said the officers are gone to Concord, and I will send word thither. I am full with you that we ought to be serious, and I hope your decision will be effectual. I intend doing myself the pleasure of being with you to-morrow. My respects to the Committee. I am your real friend,

JOHN HANCOCK."

The politeness, culture, and despatch of the opulent young merchant and patriot are apparent in this hastily penned reply. One need not draw much upon his imagination to see the beautiful Dorothy Quincy sitting by in the quiet solicitude of her high-bred dignity.

The master of the house and entertainer of these noted guests, Rev. Jonas Clark, alludes to three different messages received at Lexington that evening; viz., a verbal one, a written one from the Committee of Safety in the evening, and between twelve and one an express from Dr. Warren.

It is the last message that the poet has made familiar to all. One of the messages we must believe was brought by William Dawes, who went out from Boston, through Roxbury, at about the same time that Revere left by the way of Charlestown.

The intelligence thus brought to the guests at the Lexington parsonage was not only for them, but for the whole country, and no delay was made in spreading the alarm.

The presence of British officers scouting about the country that spring was a very common thing; but the large number on the 18th, and the lateness of the hour, led to the conclusion that their purpose was to return, under cover of the night, and capture Hancock and Adams, whose offences, it was said by Gage in his proclamation of June 12, "are of too flagitious a nature to admit of any other consideration than that of condign punishment."

"As for their king, that John Hancock

And Adams, if they're taken,

Their heads for signs shall hang up high,

Upon the hill called Beacon."

This apprehension of the Lexington people had brought together a company of men well armed, who made up the guard around Rev. Mr. Clark's house, in command of Sergeant Munroe. Three of their number, Sanderson, Brown, and Loring, went on towards Concord to ascertain and give information of the British officers; but while in the town of Lincoln, between Lexington and Concord, they were captured. Revere and Dawes, after refreshment, started on towards Concord, not knowing the fate of those who had preceded them. They were soon joined by Dr. Prescott of Concord, who was returning to his home after spending the evening with Miss Mullikin, at her home in Lexington. He was an earnest patriot, and entered heartily into the plans of his chance friends. Before coming to Concord line they were met by the same British officers, armed and equipped, who demanded their surrender. Prescott, being familiar with the roads, leaped a stone wall, escaped, and carried on the alarm to his townsmen. The prisoners were taken back towards Lexington, threatened and questioned, but given their freedom when the alarm bells of the country towns so frightened the British officers that they made haste for their escape.

With these general facts plainly in mind, the reader must be prepared to consider the approach of the invading army, their reception at Lexington and Concord, and see what the other towns had to do about it.

The soil of Lexington drank up the first blood shed in the cause of freedom on that April morning; and Concord was the point on which the forces of the colonists and of the king were focussed -- the former bent on protection, and the latter on destruction. It was there that the first forcible resistance to British aggression was made.

By reason of the events of that morning these towns became famous throughout the world, and pilgrims have journeyed thither for more than a century.

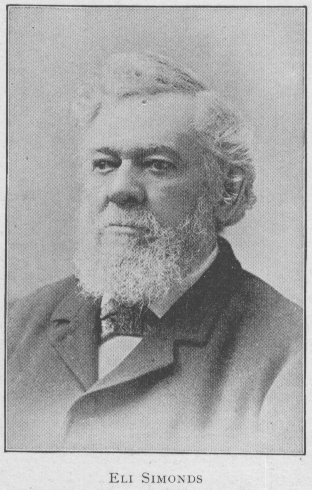

Figure

5: Eli Simonds

Facts of civil history and domestic life, having been introduced incidentally, will not detract from the interest of the story.

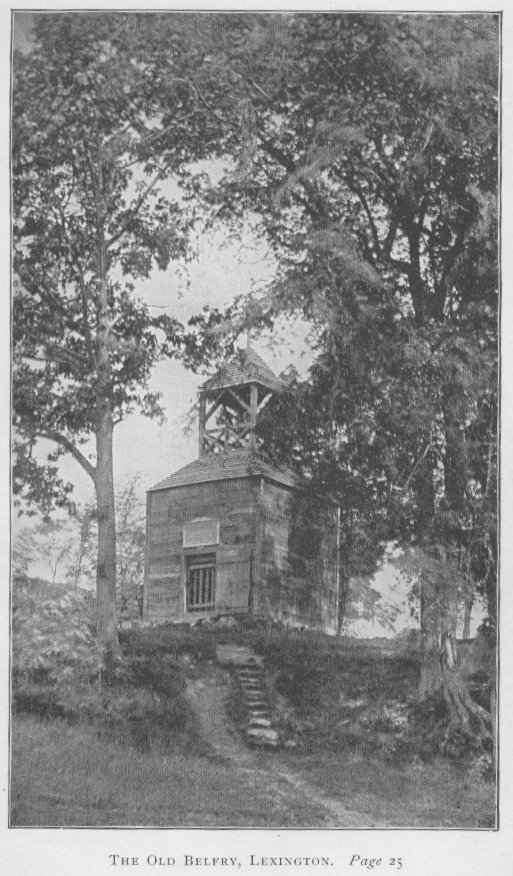

"Come up into the old belfry," said my friend of fourscore years, as we strolled across the beautiful green in the centre of Lexington.

Uncle Eli Simonds is well fitted to act as guide in this part of historic Middlesex. He is among the last of the native born of Lexington who have heard the narratives of the early days from the lips of those who participated. He has been to the place of sacrifice, hand in hand with those who were actors in the opening scene of the Revolution. Eli Simonds has not only the advantage of a birthright in the town of Lexington, but he came of a long line of ancestry who made a settlement there when the territory was known as Cambridge Farms.

Figure

6: The Old Belfry, Lexington

To those accustomed to the lofty belfry of the present time, the rude structure at Lexington, somewhat back from the village street, seems diminutive, and of itself presenting but little attraction. While climbing to its present situation Uncle Eli said, "This was erected on this hill in 1761, removed to the common in 1767, and was known to our ancestors as the 'bell free.' In it was hung the bell provided through the generosity of Mr. Isaac Stone.

"It sounded the alarm over the hills and through the vales on the memorable morning of April 19, 1775; and it served the people in joy and sorrow in that position until 1794, when the new meeting-house put forth a steeple of its own, and the bell was raised to its loft. Then the belfry was sold. It was so soon after the battle waged about its walls that no one had aroused sentiment enough to suggest its preservation. In fact, the time had not yet come for the erection of a memorial, upon the spot where fell 'the first victims to the sword of British Tyranny and Oppression.'

The martyrs were sleeping in the rude graves where they were placed by the stricken town, before it was known 'whether their blood would fertilize the land of freedom or of bondage.' But the fates had decreed that the old belfry should be preserved, which was accomplished through the purchase of the tottering house by John Parker, son of the gallant captain of the Lexington minute-men.

"It was removed to the Parker farm, some two and a half miles away, and there used as a mechanics' workshop. It was there that I became familiar with its stout frame, cut doubtless from the primeval forest, and made from trees that may have had the blazes of the pioneer's axe. Neither the house nor barn on the Parker estate afforded such general attractions as the old, belfry offered to young and old."

It was the workshop of a mechanic, John Parker, whose age exactly corresponded with that of the shop in which he plied his craft. In it the old soldiers and townsmen gathered to while away the hours of their infirmity; and in some retired nook, perhaps perched upon the huge timber in the loft where once hung the bell, were the boys of the farm, Parkers and Simondses, and their youthful associates, who there gave heed to the stories related in their hearing.

Not the least thoughtful of the bystanders in the belfry workshop was Eli Simonds, who has long been "Uncle Eli" of the neighborhood, an honored official of the town. To this mechanic, John Parker, who was well on in his teens when his father was called to arms, the reveille of that April morning never got out of those rafters. He heard the clanging of the bell, saw his father grab his musket, and hastily leave the home and family in answer to the midnight alarm. The whole town afforded no more appropriate place for the soldiers to test their memories.

Captain John Parker died, Sept. 17, 1775. He was in feeble health when at the head of the Lexington minute-men. He faced the British regulars, eight hundred strong, commanded by the impetuous Pitcairn. He also marched with a portion of his company to Cambridge on the 6th of May, and with a still larger detachment of them on the 17th of June.

After the death of the captain, the relations of the two families, Parker and Simonds, were more intimate; for Eli's grandfather became a joint owner, and the two families of children mingled by a common right at the farm.

NOT only were the old belfry's rude walls scarred by the bullets of the enemy, but its owner of later years was active on that eventful morning, and there rehearsed what he experienced, and what his brave father suffered, in all the trying scenes of the "bloody butchery."

Here Eli learned his own grandfather's story of the capture of the first prisoner of war, and of the first trophy of that day's victory.

To him and to others of the belfry's listeners, it mattered not how much great men contended for the honor of April 19, 1775, they were contented with the narratives told, without thought of preservation, and from lips that paled before the carnage about the very house in which they loved to linger, and which the sentiments of their later descendants have prompted them to return to its proper place.

At two o'clock, my father (Captain John Parker) ordered the roll of his company to be called, and gave orders for each man to load his gun with powder and ball.

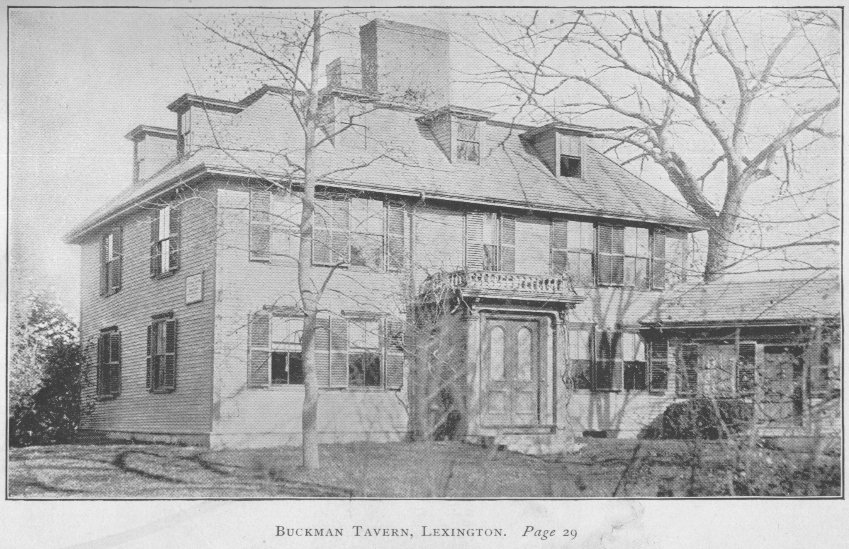

Figure

7: Buckman Tavern, Lexington

Messengers were frequently sent in order to prevent a surprise. It was Thaddeus Bowman, the last one sent out, who returned with the certain intelligence of the approach of the king's troops; others, who preceded him as detectives, had been captured, and he had a narrow escape. It was about half-past four o'clock when my father ordered the alarm-gun to be fired, and the drum to beat to arms5.

Sergeant William Munroe formed the company in two ranks, a few rods north of the meetinghouse. Father ordered the men not to fire unless fired upon. The minute-men's drum was the first heard that morning by the British soldiers ; for they had made a silent march, in hopes to catch the people napping. It was evidently taken by the British officers as a challenge. They halted, primed, and loaded, and then moved forward in double-quick time upon our men as they were forming. Some began to falter, when father commanded every man to stand his ground till he should order him to leave it, saying he would have the first man shot down who should attempt to leave his place. Then came the rush, and the shout of Major Pitcairn, "Disperse, ye rebels; lay down your arms and disperse!" Our men did not obey; and Gage repeated his order with an oath, rushed forward, discharged his pistol, and gave orders to his men to fire. A few guns were discharged; but no injury being done, our men supposed the enemy were firing only powder, and they did not return the fire. The next volley fired by the British took effect, and our men returned it. When father saw his men fall, and the rush of the enemy from both sides of the meetinghouse, as if to capture them all, he gave the order to disperse.

Figure

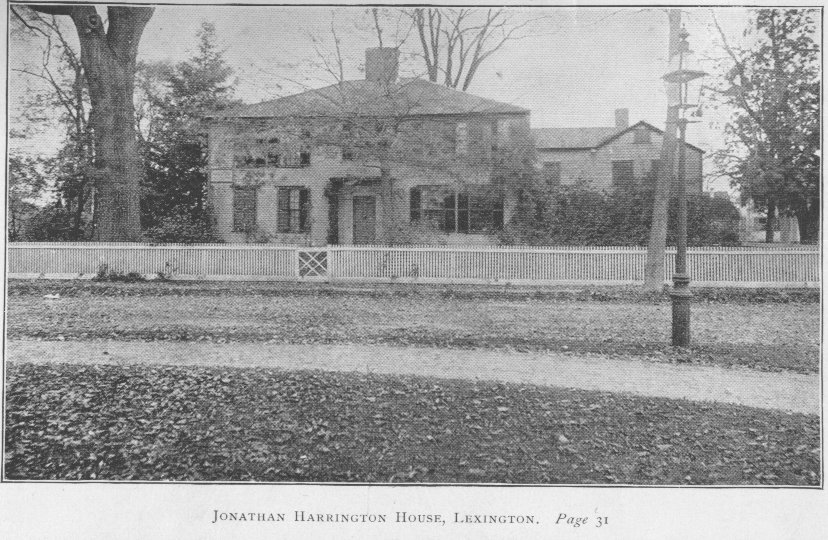

8: Jonathan Harrington House, Lexington

John Munroe did well, but loading with two balls, lost a part of the muzzle of his gun. William Tidd, first lieutenant in our company, did well. When pursued by an officer, thought to have been Pitcairn himself, who cried out to him, "Stop, or you are a dead man," he sprang over a pair of bars, made a stand and fired, and thus escaped. John Tidd fared hard. He stayed too long on the Common, and was struck down with a cutlass by a British officer on horseback. He was robbed of all his belongings and left for dead; but John lived a good many years after that day. Poor Jonas Parker! how my father mourned over him! He had always said he'd never run from an enemy. He kept his word. Having loaded his musket, he put his hat, in which was his ammunition, on the ground between his feet, ready to load again. He was wounded at the enemy's second fire, and sank upon his knees; he then discharged his gun, and while loading again was run through by a bayonet thrust which finished him. My father could hardly keep back the tears when telling of Isaac Muzzy, Robert Munroe, and Jonathan Harrington, who were killed on the Common when the company was paraded. 'Twas strange that Ensign Robert should have served in the French war, been standard-bearer at the capture of Louisburg, and then been of the first to fall by the bullets of the king's army. Poor Harrington fell in front of his own house. His wife at the window saw him fall, and then start up, the blood gushing from his wounds. He stretched out his arms, as for aid, and after another effort fell dead at his own threshold. Samuel Hadley and John Brown were killed after leaving the Common. Asahel Porter was a Woburn man; but falling here, we felt as though he was one of our own men. He was not armed, having been captured in the morning by the British on their approach to Lexington, and in trying to make his escape was shot down near the Common. Jedediah Munroe received a double share. He was not only wounded in the morning, but was killed in the afternoon. Others who were wounded were John Robbins, Solomon Pierce, Thomas Winship, Nathaniel Farmer, and Francis Brown.

"That's well done, John," cried a chorus of attentive listeners; "you had your eyes and ears open as well in your boyhood."

"You've missed those men who were in the meeting-house after powder," said Mr. Simonds.

"Sure enough," replied the mechanic, giving his workbench a thump with his huge mallet. "It's your turn now, Simonds; 'twas your father that dealt out the powder, and you may finish the story."

THE FIRST PRISONER, AND FIRST TROPHY OF THE WAR.

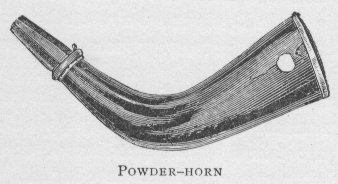

I was in charge of the town's stock of ammunition on the eventful morning. The magazine was the upper gallery of the meeting-house, and in the discharge of my duties I was there filling the powder-horns of my comrades when the regulars came into the town.

As fast as the horns were filled, their owners made haste down the stairs, and out to the line of the company for action. Of the last two who left the house, one, Caleb Harrington, was detected and killed, while the other, Joseph Comee, running in the midst of a shower of bullets, was struck in the arm, but reached a dwelling-house, and passing through it made a safe retreat.

I was left in the meeting-house with one associate, when, as it appeared, the truth flashed upon the British commander, and he determined to see what was in the house.

We heard the order, "Clear that house!" My associate glancing out saw the situation, and said, "We are all surrounded!" He then hid in the opposite gallery.

We heard the order, "Right about face!" I then determined to blow up the house and go with it rather than fall into the hands of the enemy. I cocked my gun already loaded, placed the muzzle upon the open cask of powder, and waited for their course to determine their fate and mine as well. With my heart throbbing to bursting, I heard the tramp, tramp, tramp, as the soldiers came up the steps, and the words of the commander, as his head rose above the casement, "Are there any more rebels in this house?" Tramp, tramp--they came nearer and nearer, then the word, "Halt," brought all to a stand. After an instant's pause, when the regulars, the meeting-house, myself, and comrade, were within a hair's breadth of destruction, the order was given, "Right about, march!" and they left the house.

I looked from the window, and saw the enemy form in line, and start on towards Concord; while there lay on the Common my dead neighbors, but no sign of a living comrade outside.

As soon as practicable we left the house, and in consternation went out upon the field. I soon espied a straggler from the regular army, who seemed to be somewhat indifferent to the whole situation.

He made no attempt to escape, and I took him into my custody. He was an Irishman, fully six feet in height, and manifested but little interest in the morning excursion. To my inquiry as to his delay, I found he had been overcome with liquor, lingered behind, and lost his companions. I took him to a place of safe keeping, away from the possible line of march of the army when they should return. He was thus the first prisoner captured on that day.

His musket, a good specimen of the king's arms, I also took, appropriated to my own use, and at the close of that day turned it over to Captain Parker as public property. I was not able to ascertain the remainder of the man's experience, but the gun is of interest to all.

The first trophy of the war was held by Captain Parker until his death in the autumn of that year, when it became the property of his son John, the mechanic; and it occupied a position over the door of the dwelling-house of the Parker homestead.

The gun now became in a peculiar manner a piece of common property with the Parker and Simonds families.

At the settlement of the estate of Captain Parker I bought a portion of the homestead, and my family occupied a part of the house. Large families of children had some things in common, one being the old musket6.

The story of Joshua Simonds's experience told by his son William met with the approval of the belfry listeners, inasmuch as it accounted for the men omitted by John Parker, and made clear some things about which there was a little disagreement.

Figure

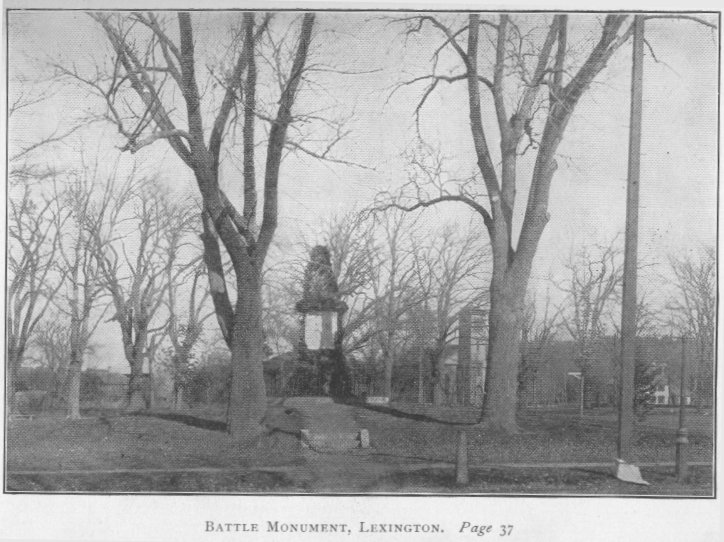

9: Battle Monument, Lexington

"Among my associates and playfellows was Theodore Parker, son of the mechanic of the belfry. To his possession in later years the musket came; and through a, provision of his last will, that musket of history found its way to the Senate Chamber of the State of Massachusetts."

INSCRIPTION ON LEXINGTON MONUMENT

SACRED TO LIBERTY AND THE RIGHTS OF MANKIND!!!

THE FREEDOM AND INDEPENDENCE OF AMERICA,

SEALED AND DEFENDED WITH THE BLOOD OF HER SONS.

THIS MONUMENT IS ERECTED

By THE INHABITANTS OF LEXINGTON,

UNDER THE PATRONAGE AND AT THE EXPENSE OF

THE COMMONWEALTH OF MASSACHUSETTS,

To THE MEMORY OF THEIR FELLOW CITIZENS,

ENSIGN ROBERT MUNROE, AND MESSRS. JONAS PARKER,

SAMUEL HADLEY, JONATHAN HARRINGTON, JR.,

ISAAC MUZZY, CALEB HARRINGTON AND JOHN BROWN,

OF LEXINGTON AND ASAHEL PORTER, OF WOBURN,

WHO FELL ON THIS FIELD, THE FIRST VICTIMS TO THE

SWORD OF BRITISH TYRANNY AND OPPRESSION

ON THE MORNING OF THE EVER MEMORABLE

NINETEENTH OF APRIL, AN. DOM. 1775,

THE DIE WAS CAST!!!

THE BLOOD OF THESE MARTYRS

IN THE CAUSE OF GOD AND THEIR COUNTRY

WAS THE CEMENT OF THE UNION OF THESE STATES, THEN

COLONIES, AND GAVE THE SPRING TO THE SPIRIT, FIRMNESS,

AND RESOLUTION OF THEIR FELLOW CITIZENS.

THEY ROSE AS ONE MAN TO REVENGE THEIR BRETHREN'S

BLOOD, AND AT THE POINT OF THE SWORD, TO ASSERT AND

DEFEND THEIR NATIVE RIGHTS.

THEY NOBLY DAR'D TO BE FREE!!

THE CONTEST WAS LONG, BLOODY AND AFFECTING.

RIGHTEOUS HEAVEN APPROVED THE SOLEMN APPEAL,

VICTORY CROWNED THEIR ARMS; AND

THE PEACE, LIBERTY, AND INDEPENDENCE OF THE UNITED

STATES OF AMERICA WAS THEIR GLORIOUS REWARD.

"IT was some days after the rehearsal of my grandfather's experience by my father," said Uncle Eli, "before the weather favored another gathering of the same company. Farmers were obliged to spend all the time in fair weather on their land, and, in fact, there were duties enough for foul weather; but there was an advantage in the interchange of ideas for the older people, and the boys, such as Sydney Lawrence, Theodore Parker, and myself, improved those opportunities.

The Parker and Simonds stories had revived an old theme; and the older belfry speakers, when at their homes, refreshed their memories by the aid of wives and parents.

John Parker himself was not averse to taking a part in the ordinary belfry gossip; and when conversation turned, as it often did, upon the subject of the Revolution, especially when others of his age were in the company, he was sure to drop his auger or mallet, push up his spectacles, and join. Being in his fifteenth year when Major Pitcairn, backed by eight hundred regulars, ordered his father with his company to disperse, John Parker was admitted to be good authority, and even Jonathan Harrington (the last survivor) would give a listening ear.

It was a catching day in haying season, dog-days are usually uncertain," said Uncle Eli, "when the belfry was filled with young and old, and conversation was at its height, a discussion of the two stories was in order, and Mr. Parker interrupted the speculation by saying, 'We had become so alarmed by the reports from the army in Boston that we hourly expected to see them rush in upon us, and rob and butcher young and old; of course, much of this was the result of exaggerated stories, yet it took but the slightest alarm to set all in motion. Why, I stood there by that wall' (pointing to the fence near by) 'on the 19th, and listened to the old bell as it clanged and clanged in this old belfry up there on the Common, and I longed to be there with father and the rest; but mother needed me, and I well remember her anxious face as she came running out of the house, with her silver spoons and other valuables, which she intrusted to my care. Now, if you will just come with me, I will show you where I secreted them.' To this call and lead of the speaker, we all responded, regardless of the falling rain, and followed down to where a decayed stump of an apple-tree was yet visible," said Uncle Eli.

"'Here is where I put it,' said Mr. Parker; there was much more of the tree here at that time, but it was hollow; and thinking of the successful hiding of the charter of the Connecticut Colony from Sir Edmund Andros, by Willian Wadsworth, I determined in my haste to intrust the household valuables to a hollow tree. I dug into the decayed heart, and pushed down my treasures, with as stealthy motion as though the whole army of the king was near at hand. So anxious were we about father's safety (for he was ill when he left the house) that I was kept a good part of the time stationed down near the highway so as to catch the slightest intimation of tiding from any one passing.' Upon returning to our belfry shelter, a hitherto earnest listener was seer to take a fresh pinch of snuff, strike a positive attitude, and take his turn in the conversation.

"Said the new speaker, 'That didn't begin with the Cutlers over to the west side. Thomas, you know, was a minute-man, and was off to answer the call, and all of the men of the family were gone. The womenfolks were so frightened that they all fled to the woods, and left the babe in the cradle.' -- 'Do tell!' cried out a half-score of voices, 'What became of it?' -- 'Oh, it lived to tell its own story,' resumed the speaker. 'I guess it was much more comfortable than were those who forgot it, sleeping away as though the redcoats were cracking jokes down in Boston camp.

"'But some of the folks at the Centre hid their silver under a heap of stones, thinking it would never be discovered there; but in the afternoon, when the regulars came back from Concord, the owner looked out from her hiding-place, and saw an officer standing directly on top of the stones. But he had little thought of what was under him, being too much absorbed in that which was about him.'

"' I declare,' said Uncle Caleb, that reminds me of the folks down to the east side, when the regulars went into the house and ransacked everything. No one dared resist, although some were where they saw all that was done, until one red-coated fellow began to tear the leaves out of the old Bible; then a boy pushed his head out from under the table, and exclaimed, "My dad 'ill give it to you, if you spoil our best Bible!" They did not meddle with the boy, thought it not worth the while, I suppose.'

"'No more than our folks did the little fifer,' said Lieutenant Munroe. 'He was a bright little fellow, and had piped away for Pitcairn as well as he could, in coming down from Concord, until an old fellow had let fly at him from his musket loaded with shot for wild geese, and had broken one of his wings; at least, there he sat, with his fife stuck into the breast of his jacket, begging for help.' -- 'We gave it to him too,' cried a voice from the perch above; `although they abused our folks, young and old.' -- 'If they hadn't thought any of us worth killing,' said Mr. Blodgett, 'more than they did Black Prince, why they would have gone right on, and we should have been as free to go to dinner as we are to-day.' With this closing remark the company decided to disperse at the ringing of the noon bell, cheered by the promise of haying weather for the rest of the day."

Weeks passed before the same company assembled again under the roof of the old belfry. But they had casually met in twos or threes in their daily walks, and some plans for the presentation of incidents in the military history had been the result.

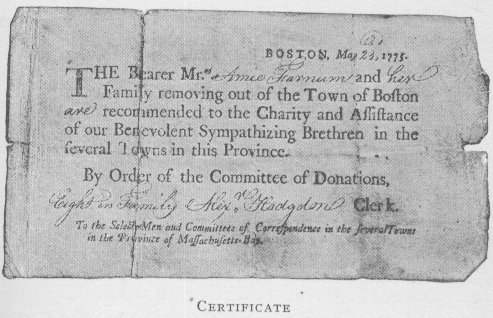

Jonathan Harrington was the leading speaker at the next meeting. He was about one year older than John Parker, and was a fifer in "that phalanx of freemen" on the 19th of April, 1775. He said, "I was aroused early that morning by a cry from my mother, 'Jonathan, get up, the regulars are coming, and something must be done.'" Mr. Harrington said, "But fighting was not the whole of it; our people had burdens to bear that are not suggested by the experiences in the field. The loss of ten of our citizens carried mourning into many families, and sorrow rested upon the hearts of a broad circle at the close of that eventful day. But that was not all. There had been a wanton destruction of property on the route of the enemy's march, and the pecuniary sacrifice had scarcely begun. Each town was called upon to share in it. With the operation of the Port Bill came grim want. Business was suspended in Boston, and sources of supply were cut off. The Whigs refused to furnish their produce to the Tories and British officers; Tories were severely dealt with when attempting to secrete supplies into Boston. Many who had been in comfortable circumstances were brought to the level of others who had been previously dependent. Many of the poor of Boston made an early removal into the country to the homes of friends, but there were others who were forced to remain and suffer. So great was their want that relief was sent from other colonies. Colonel Israel Putnam came with a drove of sheep from Connecticut to succor the inhabitants of the besieged town. Sickness naturally followed the scarcity of provision, and the condition was distressing to the extreme. The towns did all in their power for the relief of the sufferers, taking them into their own homes, and sharing their reduced income with those more needy. The extremity was so great that on May 1, 1775, the Provincial Congress ordered that they should be supported by the country towns, and the expense of removal of thousands unable to be met by themselves should also be borne by the towns. Lexington, with the others, had its share sent out. They were sent to the selectmen, and by them distributed around among the families. Each family was provided with a certificate from the committee of donations. This, which I have in my hand, was brought to my neighborhood with a family who found a good home there." The speaker paused to give each of the belfry company opportunity to examine the original from which the cut was made:

Figure

10: Certificate

He continued by saying, "After the camp was established at Cambridge, there came the demand for supplies of food and clothing, and above all there was a continual demand for necessaries for the hospitals. As each colony was at first managing its own army, it also made provision for them. But up to the time of the coming of General Washington, and the organization of the Continental army, a good deal was supplied gratuitously and voluntarily. Brave young men, unused to hardship, who were in service on April 19, and went immediately to Cambridge, were soon stricken down with disease, and either went home to die, or perished there in the illy fitted hospitals." So great was the want of the British army at one time in 1775, it is said that the town bull, aged twenty years, was slaughtered in order that the officers might have a change of diet from the salt meat to which they were reduced. The price per pound was eighteen pence sterling. We can imagine that a steak from this patriarch had staying qualities, at least.

Each town within the distance of twenty miles was called upon to furnish its quota of wood, hay, and beef for the army at Cambridge. During the entire war there were continual calls upon the towns for shirts, shoes, stockings, and blankets, and other necessaries. While the men were striving to meet the oft-repeated calls of the tax-collector, the women were busy at the spinning-wheel and loom, and there was no one exempt from duty."

"THE rehearsal of these trying experiences through which our ancestors passed was of great interest, and subdued us all to a condition of seriousness," said Uncle Eli. "But John Parker broke the spell when he said, 'The British got the worst of it. They came out here to capture Hancock and Adams, as well as to destroy the stores at Concord; but they missed their aim here, and fared hard indeed in their entire enterprise. Pitcairn probably thought he had so used our company that we would not rally again; but he got some shots from us as he came down through Lincoln, and not a few farewells were hurled at him as he left town.'"

Among the attentive listeners of the belfry workshop none attained greater eminence than Theodore Parker. Endowed with an enviable inheritance on both sides of his family, he went forth, overcoming all obstacles, as an example of Christian heroism; standing out against opposing forces as distinctly and grandly as did his honored grandsire on the field of Lexington, April 19, 1775.

It is fitting to make a digression at this point from the main line of my subject, and consider a brief sketch of the life of Theodore Parker, as given by his old belfry companion, Eli Simonds.

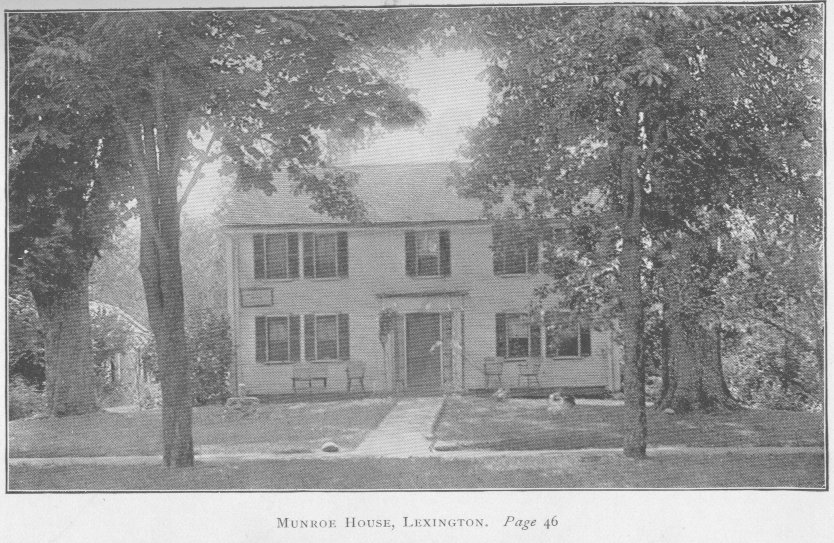

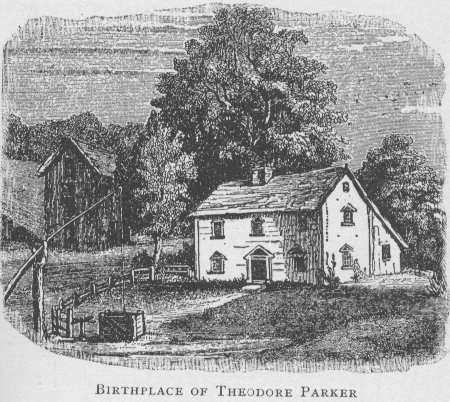

Figure

11: Munroe House, Lexington

Theodore was the youngest of eleven children of John Parker and Hannah Stearns. He was born in 1810. Eli Simonds was the tenth of a full dozen of children of William Simonds and Susan Pierce. He was born in 1817. Although seven years the junior of Theodore, the two boys had much in common. While Eli was too young to be profitably employed about the farm, he found a nook in the belfry workshop, where Theodore was trying to aid his father in the struggle for the maintenance of the family.

The humdrum of the workshop was irksome indeed to the boy Theodore, whose tastes for literary pursuits began to develop very early; but constrained by a sense of duty, he was faithful at his post, whatever it might be.

The manufacture of wood pumps was carried on by John Parker, much of the work being done in the belfry shop. The logs, cut thereabouts, were trimmed and bored by hand; the great auger used in making the circular hole in the green pine log was turned by hand. This work required a good deal of force; and Theodore detested it, and assumed very early the duties of the farm in place of that of the workshop.

Figure

12: Birthplace of Theodore Parker

Although located on a farm which might have given good returns for faithful cultivation, John Parker had but little taste or inclination in that direction, preferring the work of a mechanic Hence, both father and son pursued the line of choice, as far as circumstance admitted. "When the school was kept at the little brown schoolhouse at 'Kite End,' " said Uncle Eli, "we were always in attendance.

The schoolhouse was rude and the room unattractive; although the old fire place had been superseded by a large square stove, around which we gathered to warm our bare feet in the late autumn days, and to thaw our fingers and lunch in the winter. Theodore took but little interest in our games, but spent his odd moments over some book; but they were scarce indeed, yet such as could be obtained never escaped his faithful attention.

"We went together to the village to attend service at the meeting-house on Sundays. It was there that he had access to an old association library, from which he drew books to use at home. I have seen him open a book, when starting homeward after service, and become oblivious to all else. He would become so absorbed as to lose his bearings, and occasionally come in contact with a tree or stone wall; but tacking about, he would start on again, still engrossed with some deep study, that offered no attraction to me or other boys who were in our company.

"I well remember when, in about the year 1820, the subject of a Sunday-school was advanced. Parents as well as children were full of wonderment as to what would be studied. We had studied the Westminster Catechism at the little brown schoolhouse. The younger of us having the 'New England Primer,' a sort of juvenile catechism, in which we had learned, --

'In Adam's fall, we sinned all,'

'An idle fool is whip't at school,'

'My book and heart shall never part.'

"We also had learned the story of John Rogers, 'Agur's Prayer,' and the 'Dialogue between Youth, Christ, and the Devil.' But what could be studied at a Sunday-school was the subject for general speculation until the time set for the opening of a school. We were all there, excepting those whose parents were jealous of the school being a desecration of the Lord's day. In the great square pews we were classified, and Deacon Mullikin was our teacher. Theodore hailed the Sunday-school with delight, because it suggested study, and of course books were provided. He improved every opportunity for study, and did succeed in getting away a few weeks during the winter to a school where there were better appliances for school work. We had not ceased regarding him as 'one of the boys,' when it was whispered among the families that Theodore Parker was going to 'keep school.'

"I had begun to look upon him as a superior being, even when we were the most intimately associated, particularly when going in his company to Boston to market the peaches and other produce of the Parker-Simonds farm. We rode to market in the night, and Theodore would talk about the stars, and upon things of which I had failed to get any information. But when he began the life of a schoolmaster, I felt that I was left entirely in the rear.

"After the close of his Waltham school, it was rumored that he was not very successful; and when inquiry was made, we learned that Parson Ripley, the minister of the place, had told the secret in his prayer at the close of school. The burden of his petition was that the young man might learn to so govern himself as to be able to teach a school equal to his ability. Theodore frankly acknowledged that his greatest struggle had been in trying to govern himself.

"When Theodore Parker was pursuing a course of study in college, he spent a portion of two of his summer vacations at work on my father's farm, receiving seventy-five cents per day for his labor. It was a pleasure to be with him in the field, so interesting and elevating was his conversation.

"In after years," said Uncle Eli, "I heard that Theodore Parker was to preach at Waltham in Dr. Ripley's pulpit. I made it in my way to attend the service, which was most uplifting to me. I lingered at the close, and succeeded in getting the attention of the young preacher, my former companion, who came to me, and while our hands were clasped in the interchange of silent joy, I whispered to him, 'Do you suppose Dr. Ripley has found that you have learned to govern yourself so as to preach equal to your ability?' To this the ready wit of my old friend led him to reply, 'That was the best thing he could have done for me; for it cost me more exertion to learn to control myself than all else.'"

Mr. Simonds was in a most thoughtful mood when he closed his story of Theodore Parker by saying, "Our united homestead has passed into the possession of other families. The old squirrel musket has become the property of the State. The little brown schoolhouse has disappeared; and of all the voices echoed by the old belfry workshop, mine is almost left alone. Even the old belfry itself has gone back to serve as a monument of its April alarm in '75. Yet I have never lost my interest in my early companion. Although his voice long since was hushed, his influence will be felt long after the old belfry ceases to gratify the eye of the tourist, or its oaken frame to echo the voices of the patriots who climb to the rustic retreat of Belfry Hill."

THE word parson from its derivation - French personae, Latin persona-suggests the attitude of that official in New England. He was the person of the town. He furnished, hot merely spiritual food, but much of the intellectual and social stimulus, for the entire people.

The voice of the preacher was regarded as the voice of God. The words spoken from the pulpit passed from lip to lip as the sacred oracles of the olden times.

In many of the colonies the clergy were the only learned class, and in some instances even schooled in the medical profession, serving their people as healers of both body and soul.

The parsonage was the centre of influence, and to it resorted many people. When journeying they did not hesitate to halt at the hospitable door, and were never refused the best the house afforded. The stated salary of the minister was meagre indeed, but it represented only a part of the amount annually bestowed upon him and his family. There were many in the parish who felt it incumbent upon them to leave at the parsonage a tithing of all their produce, thereby making it possible for the good wife to respond to oft-repeated calls upon her bounty.

The clergy as a class were conservative, and inclined to favor existing institutions; but when the difficulties with the mother country assumed form, when it was necessary for action to be taken, the pastors of the so-called Puritan Congregational Churches favored the Colonial cause In some instances they joined the ranks of the minute-men and shouldered a musket, and many more served as chaplains in camp and hospital.

The parson in many country towns was an ardent Whig, notably so in Lexington and Concord. Rev. Jonas Clark of the former, and Rev. William Emerson of the latter, were so outspoken as to be known as "Patriot Priests," or "High Sons of Liberty." Much of the spirit of resistance to British oppression in those towns was attributable to their utterances.

A Tory writer says in a letter dated Sept. 2, 1774: "Some of the ministers are continually stirring up the people to resistance. It was urged that salvation depended upon signing certain inflammatory papers, when the people flew to their pens with an eagerness that sufficiently attested their belief in their pastors."

The person who could make the most lawless village ruffian cower and slink away by a look, who presided over a community of church-goers, and who had a paternal care for everything and every one in it, has passed away. So has the New England parsonage in its realistic sense been relegated to the bygones. But the house, the parsonage, in many instances yet remains, occupied in some cases by descendants in the third or fourth generation from the patriot priest of 1775. To these homes in their present well-kept condition I now invite my readers, while we there consider the footsteps of the patriots.

The Lexington parsonage has passed out of the family possession; but to its well-kept grounds all may go, and there in a well directed fancy may see the guard of minute-men in command of Sergeant Munroe as they keep their all-night vigil. Within, the rooms are reanimated by the voices of the noted patriots, Hancock and Adams; the graceful figure of Dorothy Quincy and the matronly form of Madam Hancock add dignity to the hour and occasion.

It was perfectly natural that those notable patriots should have turned their footsteps to the Lexington parsonage. They were just from a meeting of the Committee of Correspondence and Safety, and were fully aware of the precarious situation of the avowed friends of the Colonial cause in Boston, and that for them the British halter was already threatened.

It was not merely the sympathy for one cause that attracted them to that home, but kinship had allured them as well. Mrs. Clark, wife of the patriot priest, was cousin to the opulent young merchant, John Hancock. The proud step and richly embroidered costume of this guest were not strange to that home. It had been the abode of his paternal ancestry for many years. There he had spent much of his boyhood with his grandfather, Rev. John Hancock, the pastor of Lexington. Where he was, his elder friend and adviser, Samuel Adams, well might be.

Tender relations and fondest hopes account for the presence of the others in the group that night. The subject of conversation that evening can easily be imagined. "John Hancock, being in England, was present at the funeral of George II., and also at the coronation of George III., pageants congenial to his taste." He stood almost at the head of the merchants of Boston, had been an object of flattery, and strongly urged to join the royal party; but thanks to Samuel Adams, the young merchant was so decided in his course that he could say, while thinking of that princely residence and all else: " Burn Boston, and make John Hancock a beggar, if the public good requires it!" Had there been a word of doubt or any hesitancy expressed as to the righteousness of the cause in which the noted guests were champions, it would have been dissipated by the firm convictions of Rev. Jonas Clark.

The messengers from Boston were not only to warn --

"The country folk to be up and to arm,"

but to look out for the safety of Hancock and Adams. Those proud spirits could not easily be persuaded to flee from any power. But the appeal in behalf of the future welfare of the Colonies inclined them to consent; and having heard the first shots, and uttered memorable words, these noted men were conducted from one parsonage to another.

Over in Woburn Precinct, Burlington, was another parsonage. It was but a few miles away. The minister, Rev. Thomas Jones, had recently died; but his widow, well known to Rev. Jonas Clark, was an ardent Whig. There was a young minister, Rev. John Marrett, at this home, who was destined to be the successor of the deceased pastor in both pastoral and family relations. The Lexington pastor and his guests had confidence in all the occupants of the Precinct parsonage, and made haste in that direction. They made a halt at the home of James Reed, a well-known patriot, but soon pushed on; and as the gilded coach rolled up to the door of the parsonage, open arms and hearts were in anxious waiting. The patriots, with Miss Quincy, were soon comfortably ensconced in Madam Jones's best room.

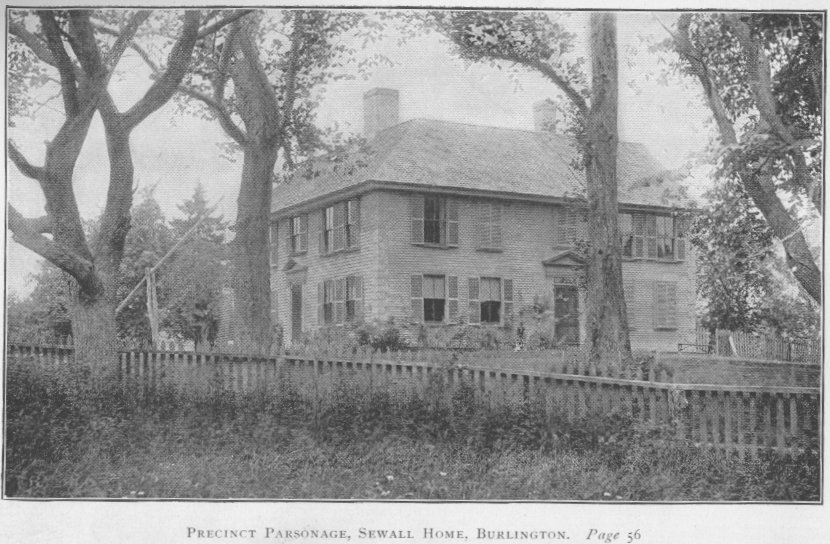

Figure

13: Precinct Parsonage, Sewall Home, Burlington

It may be of interest to the reader to know something of the history of the Precinct parsonage before following this morning's guests any farther. Leaving them seated before the crackling fire, the freshly scoured brass of the hand-irons reflecting their brilliant costumes in most pleasing pictures, we take the hand of the present owner, 1895, Samuel Sewall, of the fourth generation, and hear from him the story of the --

PRECINCT PARSONAGE.

It was purchased by Rev. Thomas Jones, my great-grandfather, in 1751. He was the second minister of the town, filling that position in the broadest sense of the term until his death in 1774. He lived to see the beginning of the Revolutionary troubles, and to make an impression as an avowed patriot, but, like Moses of old, died without entering the promised land of freedom. He was succeeded by Rev. John Marrett, who married his daughter, and hence the pastoral association continued with this house. This young minister, my grandfather, proved to be a most worthy associate of the ministers of Lexington and Concord. Besides his regular duties, he gave much attention to the poor of Boston, who were sent out to the town, sheltering some in this house. He also made frequent visits to the camp at Cambridge, and there administered to the wants of the needy. He kept a daily record of the vicissitudes of the times, and this record is one of the precious relics of our family.

Figure

14: Site of Amos Wyman House, Billerica

Strangely enough Rev. Mr. Marrett's successor, Rev. Samuel Sewall, married the daughter of his predecessor, and the charm still remained. I was the only son of Rev. Samuel Sewall and Mary Marrett; with two sisters I occupy the ancestral home. Here my children and grandchildren have been born, and are enjoying the same privilege. Hence, six generations have already occupied the parsonage, and many reminders of the first are constantly before the sixth generation." This well-kept home presents much of the same appearance that cheered the eyes of the noted guests of April 19, 1775, when Hancock's gilded coach rolled up to the door.

Old-fashioned hospitality found expression in an early spread of the best the house afforded. Madam Jones made haste to prepare a meal worthy of her guests; she was aided by Cuff, the faithful negro slave of the parsonage. A spring salmon had been passed in to the door of the Lexington parsonage in honor of the guests. This was sent on by a messenger to the Precinct, and was prepared by Madam Jones. All being ready, the guests were seated about the best table, with Rev. John Marrett as the host.

Figure

15: Parsonage Table

As soon as the immediate fright was over, Messrs. Hancock and Adams, with appetites whetted to a keen edge by the morning ride and the savory smell of the feast left so suddenly, were glad to eat cold boiled salt pork and potatoes, with rye bread from a wooden tray taken down by Mrs. Wyman from a shelf above the fireplace. Strange diet indeed for these people accustomed to the best the market afforded. It was all the variety Mrs. Wyman had, and was given cheerfully to guests whose like she had never entertained before. Her act was not forgotten. Like the widow of Zarephath, who fed the prophet Elijah, she had her reward. It is said that John Hancock presented her with a cow, when the affairs of the colony were so far adjusted as to admit of outside attention.

Figure

16: Flight of Hancock and Adams from the Precinct Parsonage

It was one of the youthful pleasures of Mr. Sewall of the present day, to accompany his honored father, Rev. Samuel Sewall, in his old age, to the Hancock mansion on Beacon Hill, Boston, and there listen to the conversation with Madam Scott, the "Dorothy Q." of 1775. An allusion to the experience related alway brought a smile to her aged face, and recalled her aunt whose name she bore, and of whom Oliver Wendell Holmes wrote:

"Grandmother's mother! Her age, I guess,

Thirteen summers, or something less;

Girlish bust, but womanly air;

Smooth, square forehead, with uprolled hair;

Lips that lover has never kissed;

Taper fingers, and slender waist,

Hanging sleeves of stiff brocade--

So they painted the little maid.

. . . . . . .

What if a hundred years ago

Those close-shut lips had answered no,

When forth the tremulous question came

That cost the maiden her Norman name;

And under the folds that look so still

The bodice swelled with the bosom's thrill?

Should I be I, or would it be

One-tenth another to nine-tenths me?"

There is another house in Burlington where the scenes of April 19, 1775, have left a lasting interest. It is the --

REED HOME.

Here Hancock's coach halted when on that memorable trip from Lexington, but soon hastened on with its company, making way for the British prisoners to be lodged here. At this home is met Mr. Edward Reed, the present owner and occupant. He was preceded in the possession by his father and grandfather, both named James Reed. "In this room," said Mr. Reed to the writer, "the prisoners captured at Lexington were held in custody. My grandfather said, 'I was making ready to go over to Lexington when I saw some of the minute-men coming with a squad of the redcoats. They brought them here to my house, and gave them up to me, informing me of the affairs at Lexington. I could not then go on in the pursuit, as I was given the custody of those prisoners. I did my duty faithfully, treated them well, as they would say to-day if they could come around; but I guess they would not want to run the gantlet of the Yankees again.'"

THROUGH the courtesy of Samuel Sewall, Esq., the present owner of the Precinct parsonage, the following extracts are made from the interleaved almanacs of his grandfather, Rev. John Marrett.

Some notes are quoted that do not tend to show the movements of the patriots altogether, but give light on the customs of the time.

January 13, 1775. Moved to Woburn. Board at Madam Jones' for 40 s. per week, and keep my horse myself.

February 8. Rode to Lexington. Lodged at my brother's last night, attended lecture at Lexington; a lecture on the times. I began with prayer. Mr. Cushing preached from Psalm 22: "He is the Governor among the Nations." Mr. Clark concluded with prayer.

March 6. Prayed at March meeting. Rode to Lexington.

March 7. Lodged last night at Brother's. Spent day at Lexington. Attended training there. At night rode home,

March 21. Training. Viewed arms.

March 27. Bottled cider; 11 dozen and one bottle.

April 4. (Tuesday.) Rode to Wilmington and Reading. P.M. Heard Mr. Stone (of Reading) preach a sermon to the minute-men. Returned to Wilmington; lodged at Mr. Morrill's, (the minister).

April 8. People moving out of Boston on account of the troops.

April 9. (Sunday.) Mr. Marston came up from Boston to get a place here for his wife and children.

April 19. Fair, windy & cold. A Distressing day. About 800 Regulars marched from Boston to Concord. As they went up, they killed 8 men at Lexington meeting-house; they huzza'd and then fired, as our men had turned their backs (who in number were about one hundred); and then they proceeded to Concord. The adjacent country was alarmed the latter part of the night preceding.

The action at Lexington was just before sunrise [showing that the paster kept an eye on all military preparations]. Our men pursued them to and from Concord on their retreat back; and several killed on both sides, but much the least on our side, as we pickt them off on their retreat. The regulars were reinforced at Lexington to aid their retreat by 800 with two field pieces. They burnt 3 houses in Lexington, and one barn, and did other mischief to buildings. They were pursued to Charlestown, where they entrenched on a hill just over the Neck. Thus commences an important period.

April 20. Rode to Lexington and saw the mischief the Regulars did, and returned home.

April 21. Rode to Concord. The country coming in fast to our help.

April 22. All quiet here. Our forces gathered at Cambridge and towns about Boston. The Regulars removed from Charlestown to Boston day before yesterday.